Calcium Sources For Your Baby

Updated May 13, 2023

This page helps you discover the best calcium sources for your baby and learn more about your baby’s calcium requirements.

Why your baby needs calcium

Contrary to popular belief, calcium isn’t JUST good for the bones – it actually plays an important part in lots of functions of the human body.

In fact, it is the most abundant mineral in our bodies.

Over 99 per cent is stored in our bones and teeth and the rest stored in other parts of the body, including muscles, blood and the fluid in between cells, where it acts as a ‘messenger’ for the central nervous system.

Throughout life, our bones undergo a lot of changes!

From birth, then throughout childhood and adolescence, a great deal of bone formation takes place.

A lack of calcium in infancy can lead to rickets, a conditions where the bones soften and may become deformed or may break easily.

Our bodies continue to add bone mass until the age of 30, when we achieve ‘peak bone mass’.

After that, things may begin to go downhill as our bones start to break down (this is known as resorption).

As we age, the rate of resorption exceeds the rate of formation – and this leads to bone loss.

Building strong bones from infancy, therefore, not only protects against rickets but also plays a huge part in delaying bone loss in later life.

A lack of calcium is also believed to contribute to diseases like hypertension, kidney disease, heart disease and – possibly – cancer of the colon.

How much calcium does my baby need?

If you’ve ever searched for the answer to this question before, you may have been baffled by figures ranging from 210mg (milligrams) per day for babies from 0-6 months and 270 mg per day for babies from 6-12 months – to the higher figures of 600mg per day for 6-12 month infants.

So why the difference?

Well, the lower set of figures was established for breast fed babies – and the higher set for those babies receiving formula (more about that later).

There are also small differences in recommendations from one country to another.

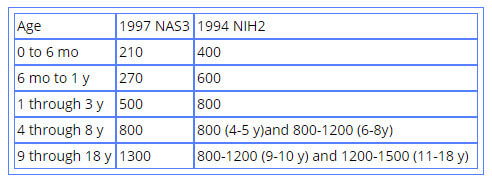

The following guide to the Calcium Requirements of Infants, Children, and Adolescents from the American Academy of Pediatrics shows both the lower and higher figures.

TABLE 1 Dietary Calcium Intake (mg/d) Recommendations in the United States2,3*

* Recommended intakes were provided in different forms by each source cited. The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) released Recommended Dietary Allowances until 1997. In 1997, it chose to use the term adequate intake for the recommendations for calcium intake but indicated that these values were to be used as Recommended Dietary Allowances. The NIH Consensus Conference did not specify a specific term but indicated that these values were the “optimal” intake levels. Dietary recommendations by the NAS are set to meet the needs of 95% of the identified population of healthy subjects. The NAS guideline should be the primary guideline utilized. For infant values, the 1994 NIH Consensus Conference indicated values for formula-fed infants, whereas the 1997 NAS report used the infant fed human milk as the standard.

is milk enough?

Milk – either breast milk or formula – meets your baby’s nutritional needs for much of his first year… and that includes his calcium requirements.

Breast milk is actually lower in calcium than formula – but that’s because the calcium in breast milk is much more ‘bioavailable’ to your baby (which means it’s more easily absorbed).

Because calcium from formula is LESS easily absorbed, then its concentration has to be greater (this is also true of the iron levels in breast milk and formula).

And the good news is that breast milk always contains the right amount of calcium for baby – even if Mum does not have enough in her diet.

Incidentally, babies have a wonderful capacity for absorbing calcium (around 60% of available calcium), precisely because it’s so important for the formation of their bones.

Sadly, this capacity for absorption decreases with age.

Calcium sources – solid foods

Towards the end of baby’s first year, solid foods begin to replace milk as his main source of nutrition.

It’s at this point – then throughout childhood and beyond – that you need to ensure the foods you give your little one provide enough calcium to meet his needs.

Good calcium sources for your baby

Milk

Milk remains a good source (but by no means the ONLY source) of calcium throughout life.

Calcium from milk is easily absorbed and milk products are generally popular with children (experts even recommend adding a little chocolate syrup for those less willing to drink milk – this is still healthier than drinking soda instead!)

Soy Milk

Some brands are better than others, so it’s important to read the label).

Cheese

Cheese is a great way to get calcium into your baby as it’s very easy to incorporate into meals (it tastes great sprinkled over cooked veggies, for example).

In addition, people who can’t tolerate other dairy products often do better with cheese.

This is because the milk protein that can cause problems breaks down as the cheese matures.

When can my baby eat cheese and which are the safest cheeses?

Yogurt

The calcium from yogurt is easily absorbed and, like cheese, yogurt is often better tolerated than other dairy products by sensitive individuals.

Fortunately, yogurt is also a very popular food with babies!

Learn how to make your own yogurt here!

Tofu

Tofu processed with calcium sulfate – a calcium salt – is a good source of calcium.

But tofu processed with a NON calcium salt is not a significant source of calcium.

Of tofu processed WITH calcium sulfate, the firm variety is a better source of calcium than the soft.)

Other calcium sources include...

- black eyed peas

- lentils

- sardines (our babies loved a little sardine mashed on toast!)

- collard greens and spinach (although these plants have a high calcium content, it is less well absorbed than from other foods – see the notes below about calcium absorption)

- kale

- broccoli

- okra

- salmon

- cottage cheese (try mixing it with fruit puree if your little one refuses it!)

- squash (summer and winter – see our butternut squash baby food ideas here)

- oranges (1 year+)

- calcium-fortified orange juice

- calcium-fortified cereal

- chickpeas/garbanzo beans

- pinto beans

- raisins

- prunes

- swede/rutabaga

- amaranth (you can read more about amaranth and other nutritious grains here)

- watercress

- parsley

It is also possible to derive calcium from hard water if you live in a hard water area.

How to help your baby absorb the calcium from his food

Offering calcium-rich foods is one part of influencing your baby’s calcium levels, but there are other factors that affect just how much calcium your baby absorbs.

Vitamin D

His body needs vitamin D to absorb calcium efficiently (you can read more about making sure your baby gets enough vitamin D here)

Don’t give too many calcium-rich foods at one meal

It seems like this would be the natural thing to do, doesn’t it, yet the amount of calcium absorbed from the digestive tract GOES DOWN as the amount of calcium consumed at one meal INCREASES.

Instead, offer small amounts of calcium-rich foods on a regular basis.

Remember that the calcium is some foods is hard to absorb

Some plants contain substances called oxalic and phytic acids.

These bind to the calcium contained in the plant, preventing it from being properly absorbed by the body (please note, though, that they only bind the calcium from the plant itself and do NOT affect the calcium absorption from other foods consumed along with it).

Examples of foods containing oxalic or phytic acids are rhubarb, collard greens, spinach, sweet potatoes, beans, whole grain bread, seeds and nuts.

How the body loses calcium

The human body loses calcium in the urine, in sweat and in faeces.

Too much sodium (salt) in the diet increases the amount of calcium that the body loses.

Another problem can be consuming too much protein.

When protein is digested by the body, acids are released into the bloodstream.

Your body neutralizes these acids by drawing on calcium from the bones.

Protein from animal sources is believed to cause more leaching of calcium than protein derived from vegetable sources.

Calcium and the vegetarian/vegan baby

Some sources suggest that babies on a vegetarian diet may be at risk of reduced calcium levels, because they may eat more of the plants containing oxalic and phytic acids that we referred to above.

On the plus side, however, the reduced calcium absorption from these plants may well be balanced by the fact that vegetarian babies do not consume as much protein (particularly, of course, meat protein) as their meat-eating counterparts.

This results in less of the leaching of calcium from the bones associated with the digestion of protein.

Still, it’s a good idea to discuss the requirements of your vegetarian baby with your child’s doctor.

Babies on a vegan diet may be at risk of low calcium levels because they do not consume dairy products.

It’s important, therefore, to ensure that the diet of a vegan baby contains lots of alternative calcium sources from the list above.

Again, you should consult your doctor to ensure that your baby is receiving enough calcium in his diet.

Does my baby need a calcium supplement?

Calcium supplements are rarely recommended for babies. The AAP states that:

No available evidence shows that exceeding the amount of calcium retained by the exclusively breastfed term infant during the first 6 months of life or the amount retained by the human milk-fed infant supplemented with solid foods during the second 6 months of life is beneficial to achieving long-term increases in bone mineralization.

The need to provide calcium supplementation to older children has not been adequately studied.

However, as the AAP quite rightly points out

…Perhaps of most importance in this age group is the development of eating patterns that will be associated with adequate calcium intake later in life.

4 quick ways to increase your baby’s calcium intake on a regular basis

- Offer him yogurt, either mixed with his favourite fruit puree or as a delicious dip with fruit or veggie sticks.

- Sprinkle grated cheese on to cooked veggies, pasta and soup. Offer your little one fingers of cheese on toast (grilled cheese) and offer pieces of cheese as a finger food.

- If your older baby refuses to drink milk, try freezing it to make milk lollies (popsicles) – they’re far more tempting! Add some fruit puree for extra flavour!

- Stir milk into mashed potatoes, make milky puddings and – if you use any types of instant cereal – make them with milk instead of water.

Source:

Office of Dietary Supplements – Calcium

More articles and recipes…

Homemade yogurt cheese – a great source of calcium

How much protein does my baby need?